Inside the surveillance software tracking child porn offenders across the globe

BOCA RATON, Fla. — In December 2016, law enforcement agents seized computers and hard drives from the home of Tay Christopher Cooper, a retired high school history teacher, in Carlsbad, California. On the devices, digital forensic experts found more than 11,600 photos and videos depicting child sexual abuse, according to court documents.

Among the videos was one showing a man raping a toddler girl, according to a criminal complaint.

“The audio associated with this video is that of a baby crying,” the complaint states.

Police were led to Cooper’s door by a forensic tool called Child Protection System, which scans file-sharing networks and chatrooms to find computers that are downloading photos and videos depicting the sexual abuse of prepubescent children. The software, developed by the Child Rescue Coalition, a Florida-based nonprofit, can help establish the probable cause needed to get a search warrant.

Cooper had used one of the file-sharing programs monitored by the Child Protection System to search for more than 200 terms linked to child sexual abuse, according to the complaint.

Cooper was arrested in April 2018 and pleaded guilty to possession of child pornography. He expressed remorse, according to his attorney, and in December 2018 he was sentenced to a year behind bars.

Cooper is one of more than 12,000 people arrested in cases flagged by the Child Protection System software over the past 10 years, according to the Child Rescue Coalition. The Child Rescue Coalition’s technology is used by about 8.500 law enforcement investigators in all 50 states. Now the nonprofit wants to work with social media and applications platforms.

The tool, which was shown to NBC News earlier this year, is designed to help police triage child pornography cases so they can focus on the most persistent offenders at a time when they are inundated with reports. It offers a way to quickly crack down on an illegal industry that has proved resilient against years of efforts to stop the flow of illegal images and videos. The problem has intensified since the coronavirus lockdown, law enforcement officials say, as people spend more time online viewing and distributing illegal material.

The Child Protection System, which lets officers search by country, state, city or county, displays a ranked list of the internet addresses downloading the most problematic files. The tool looks for images that have been reported to or seized by police and categorized as depicting children under age 12.

The Child Protection System “has had a bigger effect for us than any tool anyone has ever created. It’s been huge,” said Dennis Nicewander, assistant state attorney in Broward County, Florida, who has used the software to prosecute about 200 cases over the last decade. “They have made it so automated and simple that the guys are just sitting there waiting to be arrested.”

The Child Rescue Coalition gives its technology for free to law enforcement agencies, and it is used by about 8,500 investigators in all 50 states. It’s used in 95 other countries, including Canada, the U.K. and Brazil. Since 2010, the nonprofit has trained about 12,000 law enforcement investigators globally.

Still, it’s a drop in the ocean of online child sexual abuse material in circulation. In 2019 alone, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children received 16.9 million reports related to suspected child sexual exploitation material online.

Now, the Child Rescue Coalition is seeking partnerships with consumer-focused online platforms, including Facebook, school districts and a babysitter booking site, to determine whether people who are downloading illegal images are also trying to make contact with or work with minors.

“Many of these platforms have a big problem of users engaging in suspicious activity that doesn’t rise to criminal behavior,” said Carly Yoost, CEO of the Child Rescue Coalition. “If they matched their user data with ours, it could alert their security teams to take a closer look at some of their users.”

But some civil liberties experts have raised concerns about the mass surveillance enabled by the technology — even before it’s connected with social platforms. They say tools like the Child Protection System should be subject to more independent oversight and testing.

“There’s a danger that the visceral awfulness of the child abuse blinds us to the civil liberties concerns,” said Sarah St.Vincent, a lawyer who specializes in digital rights. “Tools like this hand a great deal of power and discretion to the government. There need to be really strong checks and safeguards.”

‘You feel like you are going to get justice’

Rohnie Williams had waited 30 years for the news she received in November 2015: Her brother, Marshall Lugo, had been arrested on charges of possession of child pornography.

“It was exhilarating in a ‘Twilight Zone’ way,” said Williams, 41, a New York-based nurse manager. “Your heart starts palpitating. Your mouth gets dry. You feel like you are going to get justice.”

Williams got in touch with Megan Brooks, the investigator on the case in Will County, Illinois, and told her that Lugo, then a teenager, had sexually abused her from the ages of 5 to 7.

Williams had told her mother about her allegations when she was 11 on the way to a doctor’s visit after she got her first period.

“I was afraid the doctor was going to tell her I wasn’t a virgin. So I told her that,” she said.

Her mother didn’t report the allegation to the police and, according to Williams, told her daughter that if she told anybody else it would destroy the family. So Williams, like so many victims of child sexual abuse, kept quiet.

Police were led to Lugo’s mobile home by the Child Rescue Coalition’s technology, which detected the household IP address’ downloading dozens of videos and images depicting the abuse and rape of babies and children under age 12. When police searched the home, where Lugo lived with his wife and two young children, they found external hard drives storing child sexual abuse material, according to the police report.

Although too much time had passed to investigate Williams’ allegation as a separate crime, her testimony provided aggravating circumstances in Lugo’s sentencing to three years in prison following a guilty plea, according to Brooks, chief investigator for the Will County High Technology Crimes Unit, who led the case.

“Some days I feel like crap doing this job, but sometimes I have full-circle moments where it all feels worth it,” Brooks said. “This was one of those cases.”

While Williams has thrived professionally, she has struggled to forgive her brother. She spends her weekends working as a sexual assault nurse examiner, providing specialist care and forensic exams to rape victims.

“I chose to go into forensics because of what happened to me as a child, to make sure these victims had somebody taking care of them who was really invested in it,” she said.

Lugo didn’t respond to a request for comment.

‘The underbelly of the internet’

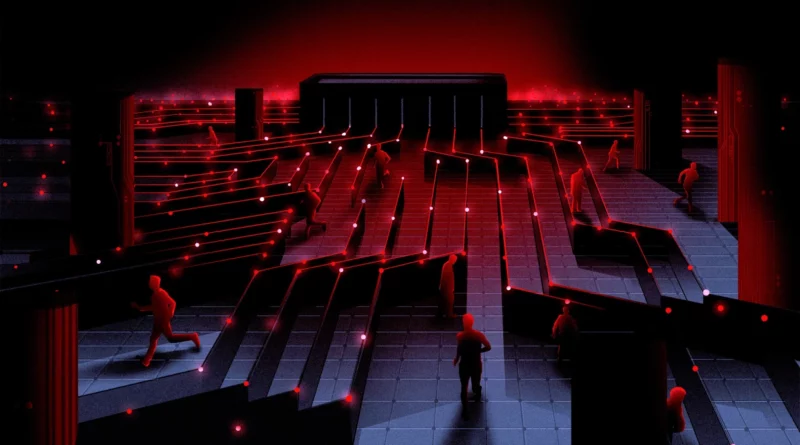

The Child Rescue Coalition is based in a low-rise, leafy business park here in Boca Raton. During a tour in February, before the coronavirus pandemic forced the staff to work from home, 10 people sat in the small office with walnut desks and striped beige carpet tiles. A framed collage of police patches hung on one side of the far wall. Next to it: a screen showing clusters of red dots, concentrated over Europe, where it was already late in the day.

Each of the red dots represented an IP address that had, according to the Child Rescue Coalition’s software, recently downloaded an image or a video depicting child sexual abuse. The dots tracked activity on peer-to-peer networks, groups of thousands of individual computers that share files with one another.

The networks, connected by software, provide an efficient and simple way to share files for free. They’re similar to the networks people use to illegally download movies. They typically come under none of the oversight of social media companies like Facebook and Twitter or file-hosting services like Dropbox and iCloud Drive. There are no central servers, no corporate headquarters, no security staff and no content moderators.

“It’s the underbelly of the internet. There’s no one to hold responsible and no security team to report it to,” said Yoost, the Child Rescue Coalition’s CEO.

The lack of corporate oversight creates the illusion of safety for people sharing illegal images.

“People who use these networks think they are anonymous,” said Nicewander, the assistant state attorney. “You don’t have to pay or give your email address to a website. You just put in your search terms, and off it goes.”

The Child Protection System was created more than a decade ago by Yoost’s father, Hank Asher. He was an entrepreneur and founder of several companies that developed tools to aggregate data about people and businesses, including a program called Accurint, for use by law enforcement.

Asher had what Yoost describes as a “rough childhood” in Indiana involving physical and verbal abuse by his father, which motivated him to “rid the world of bullies and people who picked on women and children,” Yoost said. In the early 1990s, Asher became friends with John Walsh, the co-founder of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and for the next two decades he donated his data products and millions of dollars to the nonprofit.

In 2009, Asher invited a handful of law enforcement investigators to Florida to work alongside a team of software developers at his company, TLO. Together they built the Child Protection System.

When Asher died in 2013, his daughters, Carly and Desiree, sold TLO to TransUnion on the condition that they could spin the Child Protection System into a new nonprofit, the Child Rescue Coalition.

Tracking illegal files

During the tour in February, Carly Yoost demonstrated the system, starting with a dashboard that showed a list of the “worst IPs” in the United States, ranked by the number of illegal files they had downloaded in the last year from nine peer-to-peer networks. No. 1 was an IP address associated with West Jordan, Utah, which had downloaded 6,896 “notable” images and videos.

“Notables” are images and videos that have been reviewed by law enforcement officials and determined to depict children under age 12. The material typically comes from the seized devices of suspects or reports from technology companies. That, police say, rules out some material that either isn’t illegal in every jurisdiction or isn’t a priority for prosecution.

“It’s not a teenage boy sending a picture of his girlfriend,” said Glen Pounder, a British law enforcement veteran who is the Child Rescue Coalition’s chief operating officer. “Every single one of the files we track is illegal worldwide.”

Once the images have been reviewed by authorities, they are turned into a digital fingerprint called a “hash,” and the hashes — not the images themselves — are shared with the Child Protection System. The tool has a growing database of more than a million hashed images and videos, which it uses to find computers that have downloaded them. The software is able to track IP addresses — which are shared by people connected to the same Wi-Fi network — as well as individual devices. The system can follow devices even if the owners move or use virtual private networks, or VPNs, to mask the IP addresses, according to the Child Rescue Coalition.

The system also flags some material that is legal to possess but is suspicious when downloaded alongside illegal images. That includes guides to grooming and molesting children, text-based stories about incest and pornographic cartoons that predators show to potential victims to try to normalize sexual assaults.

Clicking on an IP address flagged by the system lets police view a list of the address’ most recent downloads. The demonstration revealed files containing references to a child’s age and graphic descriptions of sexual acts.

On top of scanning peer-to-peer networks, the Child Protection System also monitors chatrooms that people use to exchange illegal material and tips to avoid getting caught.

The information exposed by the software isn’t enough to make an arrest. It’s used to help establish probable cause for a search warrant. Before getting a warrant, police typically subpoena the internet service provider to find out who holds the account and whether anyone at the address has a criminal history, has children or has access to children through work.

With a warrant, officers can seize and analyze devices to see whether they store illegal images. Police typically find far larger collections stored on computers and hard drives than had appeared in the searches tracked by the Child Protection System, Pounder and other forensic experts said.

“What we see in CPS is the absolute minimum the bad guy has done,” Pounder said, referring to the Child Protection System. “We can only see the file-sharing and chat networks.”

Police also look for evidence of whether their targets may be hurting children. Studies have shown a strong correlation between those downloading such material and those who are abusive. Canadian forensic psychologist Michael Seto, one of the world’s leading researchers of pedophilia, found that 50 percent to 60 percent of those who consume child sexual abuse material admit to abusing children.

Yoost said: “Ultimately the goal is identifying who the hands-on abusers are by what they are viewing on the internet. The fact that they are interested in videos of abuse and rape of children under 12 is a huge indicator they are likely to conduct hands-on abuse of children.”

Over time, the children depicted in the material circulating online have become younger and younger, law enforcement officials say.

“When I first started, the people depicted in images were teenagers,” said Nicewander, the assistant state attorney in Broward County, who has been a prosecutor for more than three decades. “Now the teenage pictures aren’t even on the radar anymore,” he added. “So many of the kids are under 5 or 6 years old.”

Debate over the technology

While law enforcement agencies are enthusiastic about the capabilities of tools like the Child Protection System, some civil liberties experts have questioned their accuracy and raised concerns about a lack of oversight.

In a 2019 open letter to the Justice Department, Human Rights Watch called for more independent testing of the technology and highlighted how some prosecutors had dropped cases rather than reveal details of their use of the Child Protection System.

“My view is that mass surveillance is always a problem,” said St.Vincent, the lawyer who wrote the letter. “Because these crimes are so odious, we accept aspects of searches, data collection and potential privacy intrusions we wouldn’t accept otherwise.”

Forensic expert Josh Moulin, who spent 11 years in law enforcement specializing in cybercrime, agreed.

“If you are taking someone’s liberties away in a criminal investigation, there has to be some sort of confidence that these tools are being used properly and their capabilities fall within the Constitution,” he said.

The Child Rescue Coalition said it has offered its technology, including the source code, for testing by third parties at the request of federal and state courts.

Sometimes, images flagged by the software turn out not to be on a device once police obtain a search warrant. Critics of the software say that indicates that it could be searching parts of the computer that aren’t public, which would be a potential Fourth Amendment violation.

But the Child Rescue Coalition and its defenders say the files could have been deleted or moved to an encrypted drive after they were downloaded. Every Fourth Amendment challenge of the use of the technology has failed in federal court.

Forensic experts say images in the software’s dataset could also have been miscategorized or downloaded in error as part of a larger cache of legal adult pornography.

Investigators need to be “extremely careful” to review a person’s full collection of images and pattern of behavior to see whether they were looking for illegal material or downloaded it in error, Moulin said.

Bill Wiltse, a former computer forensic examiner who is president of the Child Rescue Coalition, said: “Our system is not open-and-shut evidence of a case. It’s for probable cause.”

A growing footprint

To expand its impact, the Child Rescue Coalition has started offering its lists of suspicious IP addresses to the commercial sector, charging a subscription fee depending on the size of the company. The organization believes that if social media companies and other online platforms cross-reference the list with their own user data, they can improve their ability to detect child predators.

One of the first test cases has been a babysitting app, the developers of which did not wish to be named for fear of being associated with this type of crime. In the early days of the data matching experiment, the company found that someone had tried to sign up as a babysitter using an IP address that the Child Protection System flagged for entering a chat room with the username “rape babies,” according to the Child Rescue Coalition.

Wiltse stressed that the IP connection isn’t enough for companies to reject users altogether, particularly if it means denying them employment, as many people could be using the same Wi-Fi network.

“It’s just an indicator — something to augment your existing trust and safety procedures and practices,” he said.

Jeremy Gottschalk, founder of Marketplace Risk, a consultancy that focuses on risk management for marketplaces for goods and services, said, “If something looks suspicious, you can run that person through additional screening.”

Additional screening on a babysitting app could include checking an account for “abnormal” characteristics, such as logging in much more frequently than a typical user, or checking whether it is attached to a profile indicating that the person is willing to travel long distances for a job or is offering a rate that is well below the average.

“If you find a warning sign, you can reach out to law enforcement to give them an opportunity to investigate,” he said.

The Child Rescue Coalition believes that could help identify potential predators.

“We need people to be less scared of what would happen if they found this type of material on their platforms,” Yoost said, “and more proactive in wanting to protect children.”